|

Roger Brown, a gifted basketball player who some thought was the Michael Jordan of his era,

died March 4, 1997 in Indianapolis after a 10-month battle with liver cancer.

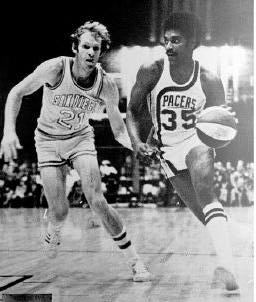

Brown, who played his freshman season at the University of Dayton and then spent a number of years in limbo because of his association with two gamblers accused of fixing college basketball games, was 54. After playing with several Dayton-area AAU teams, the 6-foot-5 Brown became the first signee of the newly-formed American Basketball Association's Indiana Pacers in 1967. In eight seasons, he led the team to three league championships.

|

|

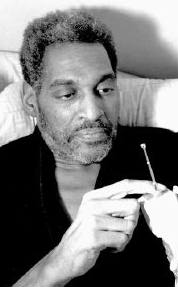

Brown in 1997 |

Published: Sunday, February 23, 1997

By Tom Archdeacon

He whispered an apology for the weariness in his voice and

the shortness of his breath. He said it had to do with the pain, the morphine

and the drowsiness.

But then, just when you weren't expecting much - when you thought the dire

circumstances were too much for the man - Roger Brown grabbed everyone by the

heart.

"I love you all,'' he said by phone in a nearly inaudible voice "Thank you

for the cards and letters and all the memories. I appreciate everything.''

As he spoke, people gathered around the speakers in the Bench Warmers

sports bar in downtown Indianapolis - site of Friday's Roger Brown Legacy Fund

Raiser. Mel Daniels, the rugged rebounder of the Indiana Pacers' past, sat in

a corner wearing cowboy boots, blue jeans and a ball cap pulled low. His lower

lip quivered and from beneath tinted glasses, big tears began to roll down his

cheeks. Finally, with his face buried in hand, he began to weep.

Back when the Pacers were winning three ABA titles and proving to be the

most exciting team in pro basketball, coach Slick Leonard had a favorite

saying. He'd gather his players in the final moments of a tight game, point to

Brown and say "Let's get this over with. Give the ball to Roger and let's go

have a beer.''

Brown was the ultimate clutch player, at his best when times were the

toughest. As George McGinnis, another star from those days, put it: "More than

any man I know, Roger Brown had the ability to seize the moment.''

People in Dayton a generation ago knew that, too. Whether they saw him when

he was in a Dayton Flyers uniform or later, when he was exiled for nearly six

years to local Ohio AAU league teams, most people would agree with Ike

Thornton.

"Roger Brown is the best basketball player Dayton has ever seen,'' said

Thornton, the former Dunbar High, Inland and Jones Brothers standout, who now

works at Monarch Marking. "I've seen (Bill) Russell and (Oscar) Robertson, and

Roger Brown was the best.''

Today, basketball still sustains Roger Brown. It gives him a foundation

when much of his life is eroding. The 54-year-old Brown is in the last stages

of inoperable liver cancer. Over the past nine months, two operations and a

series of chemotherapy treatments failed to curtail the disease. That's left

him to cope with his cancer in a one-on-one battle like he's never known.

He has no appetite and little strength. He spends much of his time in bed,

drifting in and out of a morphine-induced haze that does not mask the pain in

his stomach, chest, back, shoulders and neck.

"I don't have much time left,'' he whispered in a telephone conversation

last week from the northside apartment where - until Friday when friends

carried him to his ex-wife's home - he lived alone. "I'm not getting better.

They told me I have three months left, but now I think the cancer has gotten

to my bones. I'm not complaining, though. I'm just doing the best I can with

it.''

A week earlier, he explained: "At first, it was real tough. With sports,

you think you're invincible. Then it hits you. You find out you're vulnerable,

too.'' There was a long silence on the line, then a faint chuckle. He knew the

call was from Dayton and that meant the caller knew he'd learned that lesson

once before.

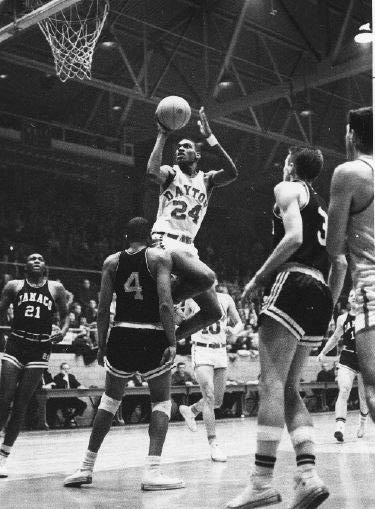

Roger Brown was a star for the University of Dayton's freshman team in the 1960-61 season. Brown and Bill Chmielewski, who also played on that team, were among the top recruits in the nation, and had Flyer fans excited. But a gambling scandal ended Brown's college career. |

Brown was figured to be one of the college game's next big stars. Local disc jockey Nick Powers went to all the Flyers games back then: "He was terrific. I idolized him. This was a god, my hero - and he wore a Dayton uniform to boot!"

But the star's vulnerability first showed a couple of months after the freshman season ended. At the time, college basketball was wracked by a gambling and point-shaving scandal thatinvolved at least 28 players from 17 different schools in 39 different games. The key figures in the case were Jack Molinas, a former NBA player who was banned from the league for gambling, and Joe Hacken, a New York hustler who was later convicted of orchestrating the scams.

Brown got pulled into the investigation because of his association he and fellow schoolboy star Connie Hawkins had with the two men. Hacken hung around New York playgrounds and asked Brown to introduce him to some prep players in the games.

Authorities figured Brown got no more than $250 for his intermediary work. Although Brown said there were no associations with the men once he got to college, authorities believed Molinas wanted the two young stars positioned in college - Hawkins was at Iowa - and he'd then try to get them to return favors.

The association became public when Brown had to return to New York from Dayton to appear in court for an auto accident he had while driving Molinas' car the summer before college.

Later, Brown and Hawkins testified at hearings involving Hacken. Neither Brown nor Hawkins was ever indicted or accused of fixing games. Still, Dayton dismissed Brown from school, just as Iowa did Hawkins. Dayton later received an NCAA probation because school officials had flown Brown back to New York three times to handle the traffic problem.

After college basketball turned its back on Brown and Hawkins, the NBA quietly blacklisted them. Both players sued the league and won $2 million settlements.

Brown has never publicly ripped UD, but there are plenty of people who aren't comfortable with the way he was treated.

"Dayton pretty much cut the cord on him,'' said "Bing" Davis, the nationally known Dayton artist and educator. "I think the school was afraid what people in town would say if it stuck up for him. But I think Dayton should have kept with its mission of helping young people. It cast him adrift.''

Powers agreed: "I think people at the university and in the Dayton media jumped the gun on him and painted him guilty before they heard the facts. If he had an attorney back then it would have been different. To be truthful, (then Flyer coach) Tom Blackburn didn't often stick up for black athletes back then.''

Herb Dintaman, the Flyers freshman coach back then, said: "Roger was robbed. Nothing was ever proven on him. The decision at the school came down fast and from higher up than I knew. I knew nothing of it. Roger was a good person who got a bad deal.''

It was worse than most people knew.

After he was pressured out of UD, Brown got a job at Inland and through his friend, Bobby Cochran, a 1960 Roosevelt grad, managed to move into Azra and Arlena Smith's home on Shoop Avenue. The Smiths helped many youngsters in Dayton, and Azra also coached the Inland and then-Jones Brothers Mortuary teams.

"When he first moved in, we got threats," Azra said. "We got a letter that said 'Get him out of your house!' Then the phone calls started. They said they knew where I worked and where my wife worked. They knew what time we left our door, when we went down Third Street, what time we got home.

"When he was sleeping, Roger used to have nightmares. He'd talk in his sleep: 'Why don't you let me alone? Please, I didn't do nothing!' I'll admit I was scared, but I didn't want to show it. Not in front of the wife and especially not in front of him. He needed to feel safe.''

Soon, the Smiths' house was his home. "We wove him into our family, but he had to follow the rules. Monday, I washed clothes and he had to help. I took him to church with me and even though he protested, I made him eat okra. He called me Hon-Bun. I called him Grandpa. He seemed old even when he was young.''

Since he was diagnosed with cancer last May, the Smiths have visited Brown several times. The more people you talk to, the more you realize the love affair between Brown and Dayton. He has several good friends in town, starting with Thornton and Cochran, who introduced him to his first wife.

As a Pacer in the late 1960s. |

In eight ABA seasons, Brown led the Pacers to three league titles. While fame finally came in Indianapolis, he never forgot Dayton. A dozen years ago, he returned to town and helped fund a program for foster children.

"He loved going over to Dayton. He never forgot the old ties there,'' said Jeannie Brown, Brown's ex-wife, who has been a lifelong companion and now maintains a hospice-like vigil.

The loyalty Jeannie spoke of showed with the Pacers, too. "The thing about the Pacers back then was that we were more a family as opposed to a team,'' said Freddie Lewis, a Pacers teammate. "You saw one of us, you saw all of us. There was a real brotherly love.''

It was that bond that brought so many of the old Pacers to Friday's fund-raiser. Lewis, now a Washington, D.C., school counselor, drove 11 hours to attend. Darnell Hillman and Jerry Harkness showed up, as did many of the current Pacers - players, coaches and management.

There were autograph sessions - $1 for a signature, with all money going to Brown's medical bills - and a silent auction of sports memorabilia broadcast by WIBC-AM radio.

"The response has been overwhelming," said Kathy Jordan, the Pacers community relations director. "(Former Pacer) Chuck Person flew in last week and gave us a $10,000 check. (Pacer coach) Larry Brown gave us $2,000. Bill Cosby called Roger. People have sent in pledges from all over the country. People had office collections and brought us money. A taxi driver challenged the rest of the drivers and all day cabs have been pulling up and dropping off donations."

Jeannie Brown listened to the litany: "This restores your faith in humanity. And Roger loves it. He's laying at home listening to the broadcasts. He's glad people still remember him.''

Roger's 21-year-old daughter listened quietly, as tears spilled from her eyes: "I love him more than anything in the world. I just wish he was going to be there to give me away at my wedding and someday see my kids grow up.''

Her mother smiled. "Your uncles will have to tell them,'' she said as she nodded toward the old Pacers - Uncle Mel, Uncle George, Uncle Freddie.

"I'd tell them if we were picking teams and there was Michael Jordan, Rick Barry, Julius Erving and Roger - and I had first pick - I'd take Roger Brown," Lewis said. "He always came through.''

That's what happened Friday night.

He got up from his sick bed, went one-on-one with the pain and prevailed. That was evident when he repeated an old Mel Daniels' claim.

"Once a ham,'' he whispered, "always a ham.''

His old teammates, his daughter, everyone managed a laugh. Given the stage one last time, Roger Brown had seized the moment.